Background

For those who manage major trauma victims, the topic of fat embolism weighs heavily on the mind. The incidence of this problem can approach 90% in patients who have sustained major injuries. If it progresses to the rare clinical entity known as fat embolism syndrome (FES), a systemic inflammatory cascade affecting multiple organ systems, morbidity and mortality are high. Accordingly, swift diagnosis and treatment of fat embolism are paramount for ensuring the survival of this patient population.

For those who manage major trauma victims, the topic of fat embolism weighs heavily on the mind. The incidence of this problem can approach 90% in patients who have sustained major injuries. If it progresses to the rare clinical entity known as fat embolism syndrome (FES), a systemic inflammatory cascade affecting multiple organ systems, morbidity and mortality are high. Accordingly, swift diagnosis and treatment of fat embolism are paramount for ensuring the survival of this patient population.

Ernst Von Bergmann, in 1873, was the first person credited with making a clinical diagnosis of fat embolism. He did this on the basis of knowledge gathered from experiments with cats 10 years previously, in which he injected them with intravenous oils. Von Bergmann later described a patient who fell off a roof and sustained a comminuted fracture of the distal femur; 60 hours after the injury, the patient developed dyspnea, cyanosis, and coma.

The diagnosis of FES is mainly a clinical one. It is dependent on clinical identification of dyspnea, petechiae, and cognitive dysfunction in the first few days following trauma, long bone fracture, or intramedullary surgery. Various laboratory studies and imaging modalities exist to aid in its discovery (see Presentation and Workup). Supportive measures are the mainstay of treatment; thus, efforts are targeted at prevention, early diagnosis, and symptom management

Pathophysiology

The exact mechanism of fat embolism and its evolution to the entity known as FES has not been fully elucidated, but a number of experimental models have been proposed. Asymptomatic fat embolism to the pulmonary circulation almost always occurs with major trauma, including elective surgical procedures such as intramedullary nailing of long bones, which has been demonstrated with echocardiography. The development of FES is rare, occurring in 0.5-11% of cases.

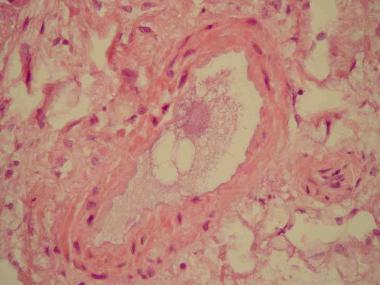

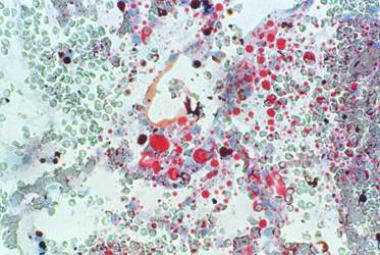

Although poorly understood, the development of FES is attributed to a series of biochemical cascades resulting from the mechanical insult sustained in major trauma. Release of fat emboli leads to occlusion of the microvasculature, triggering an inflammatory response that is clinically manifested by dermatologic, pulmonary, and neurologic dysfunction. (See the images below.)

Frozen section of lung stained with oil red O showing multiple orange red fat globules of varying sizes in septal vasculature. Image courtesy of Dr AVC Rao, Senior Lecturer in Pathology, The University of the West Indies at St Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago. Originally published in Journal of Orthopaedics (http://www.jortho.org/2008/5/4/e8/).

Pulmonary consequences of FES are clinically similar to those of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and almost always occur. They are usually the initial manifestation of FES, typically appearing within 24 hours after the traumatic insult. They result from injury to the pulmonary capillary endothelium caused by free fatty acids that were hydrolyzed by lipoprotein lipase, releasing local toxic mediators. These mediators cause increased vascular permeability, resulting in alveolar hemorrhage and edema and causing respiratory failure and ARDS.

Approximately 20-30% of the population have a patent foramen ovale; this may explain how fat emboli that pass through the pulmonary circulation end up with systemic manifestations of FES, particularly involving the brain and kidneys. As a result of the occluded cerebral vasculature, patients exhibit gross encephalopathy, localized cerebral edema, and white-matter changes.

Etiology

Causes of FES include the following:

-

Acute pancreatitis

-

Diabetes mellitus

-

Burns

-

Joint reconstruction

-

Liposuction

-

Cardiopulmonary bypass

-

Decompression sickness

-

Parenteral lipid infusion

-

Pathologic fractures

Epidemiology and Prognosis

Fat embolism occurs in 90% of all trauma patients. FES accounts for only 2-5% of patients who have long-bone fractures.

The duration of FES is difficult to predict because the syndrome is often subclinical or overshadowed by other illnesses or injuries. Increased alveolar-to-arterial oxygen gradient and neurologic deficits, including coma, may last days or weeks. Hematologic aberrations due to FES frequently are indistinguishable from those due to other causes common in these patients.

As in ARDS, pulmonary sequelae usually resolve almost completely within 1 year. Residual subclinical diffusion capacity deficits may exist. FES alone has not been reported to cause global anoxic injury, but it may contribute in conjunction with other cerebral insults. Residual neurologic deficits may range from nonexistent to subtle personality changes to memory and cognitive dysfunction to long-term focal deficits.

Outcomes in patients who develop FES are bleak if the syndrome is not identified early and aggressive supportive measures are not initiated. When action is taken early in the disease course, the prognosis is generally favorable, with a mortality of less than 10%.

Source emdedicine.com

Duc Tin Surgical Clinic

Tin tức liên quan

Performance diagnostique de l’interféron gamma dans l’identification de l’origine tuberculeuse des pleurésies exsudatives

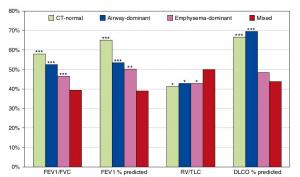

A Mixed Phenotype of Airway Wall Thickening and Emphysema Is Associated with Dyspnea and Hospitalization for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

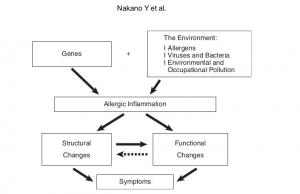

Radiological Approach to Asthma and COPD-The Role of Computed Tomography.

Significant annual cost savings found with UrgoStart in UK and Germany

Thrombolex announces 510(k) clearance of Bashir catheter systems for thromboembolic disorders

Phone: (028) 3981 2678

Mobile: 0903 839 878 - 0909 384 389