Venous malformations (VMs), like other vascular malformations, are present at birth. They are the most common type of vascular malformation, affecting 1% to 4% of individuals, and clinically appear as a bluish, soft, compressible lesions typically found on the face, limbs, or trunk

Venous malformations are composed of masses of veins and venulae of different dimensions lined by a single endothelial layer.6 Venous malformations are dependent lesions, meaning that they expand and contract based on patient positioning. They tend to grow proportionally with the child and often increase in size with puberty, hormonal changes, or infection.11 They show a predisposition to thrombosis, forming phleboliths, which are pathognomonic of VM and are diagnostic on imaging studies. Phleboliths are intralesional calcifications formed as a result of venous stasis and inflammation.12

Various manifestations of localized venous malformations. Venous malformations are bluish, soft, compressible lesions typically found on the (A,B) face, (C) limbs, or trunk.

Although US and color Doppler are first-line modalities for diagnosis, showing low flow lesions with phleboliths, MRI is most useful for defining the extent of the disease.13Angiography is also a useful modality for defining extent of disease, especially when identifying deep or small VMs, such as intracranial sinus pericranii or gastrointestinal VM, as traditional MRI and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is not as sensitive in identifying these lesions.14 Beyond imaging, it is sometimes prudent to obtain a coagulation profile if the patient has a large VM given the risk for localized intravascular coagulopathy.15

Treatment options for VM depend on both the extent of the lesion and the location. Typically, functional or aesthetic limitations will drive the initiation of therapy. Interventional radiology can deliver primary treatment such as staged sclerotherapy and embolization, or play a supportive role with pre- or intraoperative embolization. Sclerotherapy with absolute ethanol is effective for treatment of large, extensive VMs, but should be used with caution as it can damage nerves, cause skin necrosis, and induce systemic toxicity.16 17 Other common sclerosants used include 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate (STS) and bleomycin. Surgery is rarely first-line therapy, but may be considered in select situations, such as (1) to ligate efferent veins to improve the results with sclerotherapy, (2) to remove residual VM after sclerotherapy, (3) to remove lesion resistant to sclerotherapy, or (4) localized lesion amenable to complete excision (Fig. 5).18 It is important to recognize that resection can be arduous and technically demanding; thus, it should not be undertaken without a thorough discussion of all operative risks.

Lymphatic Malformation

Lymphatic malformations (LMs) are vascular channels, pouches, or vesicles filled with lymphatic fluid with a single endothelial cell lining, 75% of which occur in the cervicofacial region (Fig. 6). They were referred to as “lymphangioma” in the past, which is a misnomer because LMs lack cellular hyperplasia. Lymphatic malformations are categorized by the size of the lymphatic chamber: macrocystic (> 2 cm), microcystic (< 2 cm), or mixed. Lymphatic malformations never regress yet expand and contract based on the amount of lymphatic fluid present and the presence of bleeding or inflammation.6 These lesions are often evident at birth and appear as small, crimson dome-shaped nodules as a result of intralesional bleeding. Many macrocystic LMs can enlarge significantly leading to distortion of anatomy, especially of the soft tissues and bones of the face. Along with tissue distortion, frequent bouts of bleeding and cellulitis will dictate the need for intervention.

Most cases of LM are clinically obvious and require no imaging for diagnosis. When a diagnosis is not so clear, imaging modalities such as US and color flow Doppler are particularly useful in establishing a diagnosis.5 Ultrasound is performed to identify the characteristic cystic appearance of these lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging is helpful not only in diagnosis, but also for evaluating the extent of the disease. Classic appearance on MRI is mild enhancement of the septae and walls, which creates a characteristic enhancement pattern of rings and arcs. Magnetic resonance imaging is also useful in distinguishing microcystic versus macrocystic lesions as therapeutic modalities differ between the two.14

Treatment options for LM begin with expectant management of symptomatic lesions, such as pain control and compression for intralesional bleeding and antibiotics for infection, which can often be life threatening. Sclerosants are first-line therapy with options such as absolute ethanol, doxycycline, STS, or picibanil (OK-432).19 These agents cause irreversible damage to the endothelium, inducing local inflammation and ultimately fibrosis. The only potentially curative modality is surgical resection. The goals of resection focus on gross debulking of defined anatomic field, limiting blood loss, and minimizing damage to surrounding structures (Fig. 7). It is important to remember that complete resection is typically not possible as remaining channels will regenerate and extensive radical resection is typically performed at the expense of surrounding normal structures.2021

A 4-year-old boy with lymphatic malformation involving the (A,B) chin, (C,D) status postradical resection.

Arteriovenous Malformation

Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) represent a class of vascular malformations that develop from an identifiable source vessel called the “nidus,” which conducts an abnormal connection of arterial and venous systems.22 This type of shunt is usually present at birth, but does not become apparent until the first or second decade of life. Arteriovenous malformations may be slightly compressible and pulsatile with a palpable thrill. This type of lesion is most commonly found intracranially and can expand in response to certain stimuli such as trauma or puberty. Clinically, AVMs can appear in soft tissues or bone and are typically not accompanied by pain, but rather frequent episodes of bleeding.23 These lesions have a reliable natural history comprised of four distinct stages: quiescent, growing, symptomatic, and decompensating.24

Imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis of an AVM, but more so in operative planning. As with other vascular malformations, US and MRI can identify high flow patterns as well as determine the extent of the lesion. Lesions are often multispacial and hypervascular on color Doppler US. Magnetic resonance imaging is especially useful in defining the extent of AVMs, and typically shows numerous flow voids and hyperintense signal without an obvious mass.8 Unlike other vascular malformations, computerized tomography (CT) can be valuable, especially for bony AVMs. Angiography can also be utilized for defining the feeding and draining vessels prior to sclerotherapy or surgical intervention.5

Treatment of an AVM is based on the concept of obliteration of the nidus as this is thought to be responsible for the growth of the lesion through recruitment of new vessels from neighboring regions. Sclerotherapy and embolization remain first-line options to allow for safer intraoperative resection with less blood loss.25 Ligation of feeding vessels should never be done as this leads to rapid recruitment of collaterals and heightens vascularity. When considering resection of an AVM, it is paramount to realize that these lesions are rarely curable, but rather one should focus on disease control. Indications for intervention include ischemic pain, recurrent ulcerations/bleeding, or perturbed cardiac function.26Resection of these lesions can create large defects that may require flap coverage or formal reconstruction and should only be performed if the benefits greatly outweigh the risks (Fig. 8).

A 12-year-old boy with biopsy-proven right periorbital arteriovenous malformation (AVM) causing (A) vertical dystopia and proptosis. (B) Angiogram was obtained confirming AVM, but was not amenable to embolization due to involvement of the ophthalmic artery. (C) Given the bony involvement, CT scan was useful for operative planning. (D) A radical resection was performed with subsequent orbital roof and forehead reconstruction with alloplast. (E,F) Vertical dystopia and proptosis was improved postoperatively.

Vascular malformations are a source of great concern and anxiety not only for patients and their families, but also for the treating physicians. Proper identification as well as multidisciplinary approach is paramount for proper treatment. Understanding the clinical aspects, tools available for diagnosis, and options for interventions of each subtype of lesion will enable appropriate care to be provided and results to be maximized.

Source ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Duc Tin Clinic

Tin tức liên quan

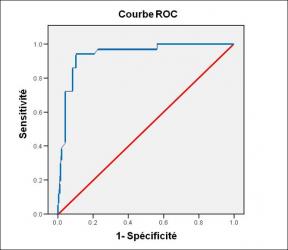

Performance diagnostique de l’interféron gamma dans l’identification de l’origine tuberculeuse des pleurésies exsudatives

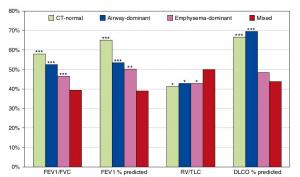

A Mixed Phenotype of Airway Wall Thickening and Emphysema Is Associated with Dyspnea and Hospitalization for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Radiological Approach to Asthma and COPD-The Role of Computed Tomography.

Significant annual cost savings found with UrgoStart in UK and Germany

Thrombolex announces 510(k) clearance of Bashir catheter systems for thromboembolic disorders

Phone: (028) 3981 2678

Mobile: 0903 839 878 - 0909 384 389