I.Postoperative Care and Instructions

I.Postoperative Care and Instructions

Postoperative care is designed to improve efficacy and minimize side effects and the risk of complications.

There is a diversity of opinion about what is necessary as no evidence supports any specific recommendations. Immediately postoperatively, almost all physicians recommend some form of compression. The most common recommendation is for class II compression stockings (30–40 mm Hg) applied immediately after the procedure and worn for 1–2 weeks. The clinical value of this practice is not substantiated by data. Anecdotally, patients feel better with the use of compression, especially during the second week when the pulled-muscle feeling occurs.

Patients are encouraged to ambulate for at least 30–60 minutes after leaving the procedure room and at least 1–2 hours daily for 1–2 weeks. Hot baths, running, jumping, heavy lifting, and straining are discouraged by many physicians for 1–2 week. NSAIDs may be taken on an as-needed basis for discomfort.

Patients are generally seen at 1 month after the procedure to assess the results by clinical examination and DUS. Some physicians recommend a follow-up DUS 24–72 hours after the procedure as surveillance for junctional thrombus extension from the treated vein into the contiguous deep vein. However, as mentioned, the yield of this early examination for identifying extension of thrombus beyond the deep junction extending into the femoral vein for GSV or popliteal vein for SSV ablation is at most 1%. Moreover, treatment of such nonocclusive extensions is controversial and increasingly conservative care is recommended. Most physicians agree that repeat DUS at about 9-12 months after the procedure ultimately determines the anatomical success of the ablation.

II.Results of ELA

General comments

ELA is safely and effectively performed using local anesthesia in an office setting requiring about 45–90 minutes of room time to be performed. Procedure times are dependent on the number of concurrent treated veins, length of segment(s) treated, and whether ancillary procedures, such as ambulatory phlebectomy, are carried out. Patient satisfaction has been reported to be very high.

.jpg)

Varicose vein before treatment with endovenous laser therapy.

Varicose vein after treatment with endovenous laser.

The total cost (cost of the procedure plus societal cost) of endovenous procedures is likely equal to or better than that of surgery. This is debatable in a hospital setting, but is almost certainly true if the ELA can be performed in a nonspecialized office setting. These techniques are being rapidly adopted and are now being performed more often than traditional HL/S in the United States.

Anatomical success rates

The anatomical outcomes following endovenous treatment include occlusion of the treated segment, early failure (complete or segmental), or late recanalization (complete or segmental). Anatomic success following ELA should result in the treated vein having no lumen and either shrink to a fibrous cord < 2.5 mm in diameter or become sonographically absent 6–12 months after treatment. Anatomical success with ELA of the GSV has been reported between 93–100%. The follow-up for these evaluations varies from 3 months to 4 years.

Fewer data are published following SSV ablation with ELA but the results are qualitatively similar to that found with GSV ablations.

Most ELA recanalizations occur in the first 6 months and all in the first 12 months following ELA. This suggests that recanalization may be related to insufficient thermal energy delivery to the target vein with resultant vein thrombosis and recanalization of the thrombus. Most early recanalizations after GSV ablation can be avoided by using laser energy greater than 80 J/cm and a continuous mode of laser energy application. Late clinical recurrence is extremely unlikely in an occluded vein that has shrunken to a noncompressible cord. Based on this and the surgical data that demonstrate the pathological events that lead to recurrence, which usually take place within 2 years, later clinical recurrences are more likely related to development of incompetence in untreated veins or vein segments (progression of disease in other veins).

To a great extent, late clinical success after ELA is predicated by the natural history of the venous insufficiency in a given patient, the ability of the treating physician to identify refluxing pathways and plan treatment (often described as tactical success) and successfully eliminate all pertinent incompetent pathways (often described as technical success), and the success of the adjunctive procedures used to eradicate any coexistent incompetent tributary veins after ELA.

With ELA, in most cases the first 1-2 cm of the treated vein beyond the SFJ or SPJ remains patent as treatment is begun just below this level. Post-ELA patency of segments less than 5 cm long beyond the junction are the most common form of anatomical failure. Clinically, in spite of this, nearly all of these patients benefit from the procedure. However, the patent stump of GSV is usually connected to a saphenous tributary, which, over time, may reflux and be the source of a clinical recurrence.

Posttreatment patency of greater than 5 cm of treated vein segments is much less common and is more likely to be associated with persistent or recurrent symptoms. Less successful closure of the proximal vein segment may be related to insufficient thermal injury to this portion that is generally of larger caliber and less likely to develop spasm during tumescent anesthetic administration and consequently more difficult to empty. As a result, it is less likely to develop good device and vein wall apposition in this segment, which is thought important for optimal vein wall energy deposition to achieve successful ablation.

Patients with a high body mass index have been shown to have a higher rate of failure with laser. The rationale for this observation is unclear, although it is known that obese patients have higher central venous pressures and a higher frequency of chronic venous disease. ELA success has been demonstrated in a retrospective data review to be independent of vein diameter in many studies. However, a prospective confirmation of this conclusion has not been performed.

III.Evaluation of Clinical Outcomes

Clinical outcomes from varicose vein ablation can be quantified by numerous reporting systems, including the Clinical, Etiologic, Anatomic, Pathophysiologic (CEAP) classification, the revised Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS), and several patient reported metrics including generic instruments such as the SF-36 and several disease-specific instruments such as the Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire (AVVQ), Chronic Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ) 2, Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study (VEINES), and Varicose Veins (VV) Symptoms Questionnaire (VVsymQ). The VVsymQ may be the best patient-reported metric because it has been approved by the FDA for use in device and drug trials.

Several studies have documented significant and durable improvements in validated assessments of quality of life following ELA, which were at least as good as or better than the improvements seen following HL/S in one study.Evaluation of the effectiveness of ELA in CEAP 4-6 patients was performed in a retrospective review of patients 6 weeks after they were treated with RFA and laser; 85% vein occlusion was noted overall, with significant improvements in the VCSS and air plethysmography (APG).

Ulcer healing has been induced after ELA. One report documented an 84% success rate with ulcer healing with a combination of either RFA or laser and microphlebectomy, with 77% of these healing within 2 weeks of the procedure.The Effect of Surgery and Compression on Healing and Recurrence (ESCHAR) study showed that removal of the refluxing superficial veins significantly reduces ulcer recurrence rates at 3 years. Treatment of incompetent perforators likely also play an important role in healing active ulcers and preventing recurrence.

Several small comparison studies have evaluated the outcomes of laser ablation and surgery. In the first to be published, 20 patients with bilateral GSV reflux were treated with conventional HL/S on one leg and HL and laser in the other and then observed for 3 months. The patients were not informed which leg received either therapy, the choice of which technique used was randomized, and all patients were treated with either a spinal or epidural anesthesia. No tumescent anesthetic was used. Early pain was similar for both procedures, although bruising and swelling were worse with surgery. All patients thought the aesthetic improvement was much better in both limbs, but 70% thought the laser limb benefited the most, 20% the surgical limb, and 10% thought they were equal. APG improvements were equivalent in both groups.

A nonrandomized, consecutive treatment comparison of conventional HL/S with general anesthesia and laser ablation of the GSV using tumescent anesthesia has been performed. The authors demonstrated that with the 36-Item Short Form Health survey (SF-36) at 1 and 6 weeks, the patients treated with laser did not suffer the decrease in quality of life seen in the surgical group at the same time. By 12 weeks, both groups had similar improvements in quality of life and in an objective assessment of the severity of their venous disease. The VCSS improvement was significant compared with the pretreatment assessment and similar for both groups of patients.

A randomized comparison of 118 limbs treated with laser and microphlebectomy and 124 with conventional HL/S and microphlebectomy compared the quality of life of the postprocedure period of both procedures. The study demonstrated significantly less postoperative morbidity for the laser procedure using the CIVIQ. In addition, patient satisfaction, analgesia use, and the duration of days before return to work were significantly better for the laser-treated group.

A randomized trial of 68 limbs treated with HL/S and 62 with laser was performed with both groups only being treated with tumescent anesthesia. The preliminary report of this ongoing study evaluated the patients up to 6 months after their procedure using a variety of validated instruments, including a visual analogue scale of pain, VCSS, AVVSS, and SF-36. Initial technical successes were equivalent. In this trial, the early bruising and pain favored laser, but by 3 months both procedures demonstrated significant improvements in all indices compared with pretreatment baselines, but no differences were seen between HL/S and laser. Five-year follow-up data from this study demonstrates no difference in the number of reoperations for recurrent varicose veins as well as improved AVVSS and several domains of the SF-36 in both patients treated with ELA and HL/S.

A randomized trial of 280 patients comparing HL/S and ELA of the GSV confirmed that both treatments resulted in significant reduction in objective severity of disease, lower VCSS scores, lower AVVQ scores, and improved quality of life. ELA also showed decreased postprocedure pain and earlier return to work than surgery.

A randomized trial of 106 patients receiving HL/S versus ELA of the SSV demonstrated similar findings to the GSV, with equal clinical benefits at 1 year, decreased periprocedural morbidity, earlier return to work, and a significant reduction in sensory disturbance.

A study by Gauw et al reported that compared with saphenofemoral ligation and stripping of the GSV, ELA (bare fiber, 980 nm) led to a higher rate of varicose vein recurrence in the saphenofemoral junction region by 5-year follow-up. Clinically visible recurrence was found in 20 out of 61 patients (33%) who underwent ELA, compared with 10 out of 60 patients (17%) treated with ligation and stripping.

Similarly, a study by Rass et al found that by median 5-year follow-up for treatment of GSV incompetence, ELA resulted in more recurrences in the operated region than did HL/S (18% vs 5%, respectively). On the other hand, the rate of different-site recurrences was greater in the HL/S group than in the ELA patients (50% vs 31%, respectively)

IV.Summary

Since its introduction, ELA has replaced ligation and stripping procedures of the GSV and SSV to eliminate reflux. The procedure has been validated to result in reliable elimination of saphenous vein reflux, is safe, well tolerated, and durable. In addition, it has been shown to produce less periprocedural pain, shortening the recovery to allow for earlier return to work.

Source emedicine medscape.com

DUC TIN SURGICAL CLINIC

Tin tức liên quan

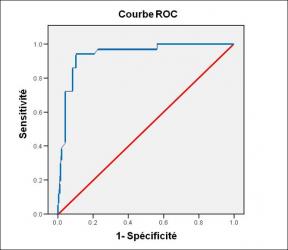

Performance diagnostique de l’interféron gamma dans l’identification de l’origine tuberculeuse des pleurésies exsudatives

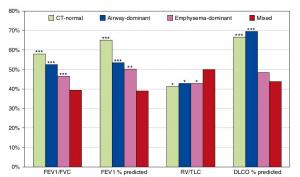

A Mixed Phenotype of Airway Wall Thickening and Emphysema Is Associated with Dyspnea and Hospitalization for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Radiological Approach to Asthma and COPD-The Role of Computed Tomography.

Significant annual cost savings found with UrgoStart in UK and Germany

Thrombolex announces 510(k) clearance of Bashir catheter systems for thromboembolic disorders

Phone: (028) 3981 2678

Mobile: 0903 839 878 - 0909 384 389